|

|

|

Феромоны

Материал из Википедии — свободной

энциклопедии

Феромо́ны — собирательное название веществ — продуктов внешней

секреции, выделяемых некоторыми видами животных и обеспечивающие химическую коммуникацию между

особями одного вида. [править]История открытия

Первыми

феромоны удалось обнаружить группе немецких исследователей, которые в 1956 году сумели

выделить из желез самок шелкопряда вещество, привлекавшее самцов того же

биологического вида. Полученное вещество было названо бомбикол — из-за

латинского названия шелкопряда, Bombyx mori. [править]Классификация феромонов

Феромоны

модифицируют поведение, физиологическое и эмоциональное состояние или метаболизм других особей того же вида. Как правило,

феромоны продуцируются специализированными железами. По

своему воздействию феромоны делятся на два основных типа: релизеры и

праймеры. Релизеры — тип феромонов, побуждающих особь к каким-либо

немедленным действием и используются для привлечения брачных партнёров,

сигналов об опасности и побуждения других немедленных действий. Праймеры

используются для формирования некоторого определённого поведения и влияния на

развитие особей: например, специальный феромон, выделяемый пчелой-маткой. Это

вещество подавляет половое развитие других пчёл-самок, таким образом

превращая их в рабочих пчёл. В

качестве отдельных названий некоторых типов феромонов можно привести

следующие:

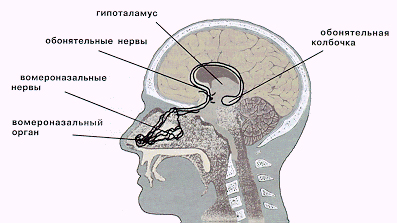

[править]Феромоны, или другими словами, половые аттрактанты - это душистые летучие вещества с небольшой молекулярной массой, выделяемые в малых количествах практически всеми представителями животного мира. Эти вещества, попадая в воздух, воспринимаются чувствительными рецепторами органов обоняния, которые передают "возбуждающий" сигнал в кору больших полушарий. (Существует дополнительный орган обоняния — вомероназальный — две крошечные трубочки, расположенные в основании носовой перегородки, вблизи косточки под латинским названием «vomer». Этот орган-малыш улавливает только феромоны — более увесистые, чем молекулы душистых веществ, пахучие вещества, через которые передается важнейшая информация.) Феромоны человека участвуют в регуляции синтеза половых и иных гормонов, а вомероназальная система непосредственно влияет на формирование мозга человеческого эмбриона. Основанные на человеческих запахах вариации природных ароматов можно с успехом использовать как средства повышения потенции, усиления чувственности, устранения проблем аноргазмии (поскольку ароматы оказывают стимулирующее действие на вомероназальный орган. Все эти ароматы, содержат «магические молекулы», которые, помимо стимуляции сексуальной сферы, являются мощными природными антидепрессантами. Они во многом определяют сексуальную привлекательность женщин и мужчин. Запахами эти феромоны практически не обладают, но действуют в очень малых количествах на рецепторы вомеронозального органа, а через него на функции, которые контролируются гипоталамусом (половое желание, половая готовность, глубокие эмоции, уровень гормонов, зрелость, агрессия или покорность и др.). 10

фактов о феромонах

1. Забытый язык. Когда-то люди в совершенстве

владели языком запахов. И хотя он давно уже нами забыт, его смысл хранит

генетическая память.

Вот скажите, почему ничем не примечательный

мужчина может показаться нам таким обаятельным? А что заставляет обходить

десятой дорогой человека, охваченного печалью или злостью? В обеих случаях

причиной являются микроскопические вещества под названием феромоны.

В отличие от богатых ароматов свежеиспеченного

пирога, «эмоциональные запахи» мы не осознаем, однако это ничуть не мешает

этим серым кардиналам тайно управлять нашей сексуальностью и настроением.

Феромоны улавливает крошечный вомероназальный

орган, расположенный в носовой перегородке, и пересылает «для перевода» в

специальный отдел головного мозга. Когда мы раздражены или плохо себя

чувствуем, испускаем репелленты. Этот запах не нравится окружающим, поэтому

они всячески стараются нас избегать. А вот ощущая душевный подъем или

уверенность в себе, мы излучаем аттраканты. И нас замечают, любят, нам

симпатизируют!

2. Нос всему голова. Читать послания феромонов

умеют 98 процентов людей. Среди них попадаются настоящие «полиглоты».

Например, слепой пианист Джордж Ширинг на запах мог определить степень

привлекательности вошедшей в комнату дамы. Многие с завязанными глазами

безошибочно отберут одежду, принадлежащую их сексуальному партнеру. А

женщины-полицейские порой отличаются столь тонким обонянием, что чувствуют

присутствие преступников по одному только… исходящему от них запаху страха.

3. Парное сочетание. Почему в одного мужчину мы

влюбляемся с первого взгляда, а другой вызывает отвращение, будь он хоть

трижды Брэд Питт! Все зависит от того, подходит ли нам запах его иммунной

системы. Мужчина со сходным иммунитетом вряд ли понравится. В нашей

генетической памяти тут же предупредительно мигнет красный сигнал опасности:

идентичный обмен веществ и генотип - не слишком удачное «наследство» для

будущего ребенка.

Кстати, по этой же причине не приветствуются браки

между родственниками. Их иммунные системы похожи, как две капли воды, и шансы

двум «бракованным» генам встретиться увеличиваются. Зато чем больше мужчина

нравится, тем сильнее его иммунотип отличается от вашего и тем лучший

генетический набор получит ребенок. Где-то в центральной Африке есть племя, в

котором до сих пор выбирают супругов по «нюху». И как утверждают

исследователи, почти никогда не ошибаются. Ну а если хотите убедиться в

правильности своего выбора, поцелуйтесь с любимым. Приятные ощущения не

пропадают? Не сомневайтесь, перед вами суженый.

4. Секрет Мэрилин Монро. Декольтированное платье,

пухлые губы, особый состав краски для волос? Вовсе нет. Люди, которые входят

в ранг секс-символов, выделяют в воздух больше половых феромонов. А те

гипнотически влияют на умы и сердца противоположного пола. Ученые полагают,

что особенно интенсивно секс-феромоны продуцируют блондинки и рыжие. Между

прочим, 10 процентов мужчин тоже имеют в своем поте вещества, которые делают

их особенно привлекательными для дам. А их рядовые собратья с весьма

заурядным набором феромонов недоумевают: почему этот коротышка Том Круз

кажется женщинам таким сексуальным?

5. Карта тела. Разумеется, каждая клеточка нашего

тела не источает феромоны. Они «обитают» на строго отведенной для них

территории. У мужчин, например, мощнейший источник феромонов — сперма.

Сексологи заметили, что у женщин, не чувствующих ее запах по причине

расстройства обоняния, страдает сексуальность. Большое количество феромона

андростерона выделяется вместе с потом. Источником феромонов является кожа,

волосы и подмышечные впадины — причем как у мужчин, так и у женщин. А самый

мощный женский феромон — копулин — присутствует в выделениях вагины. Не

случайно во многих восточных школах, практикующих науку любви, женщинам

советовали вместо духов пользоваться… насыщенными феромонами «соками тела».

6. Ароматы любви. Самое простое приворотное

средство — это духи, обогащенные половыми аттракантами. Купить такое «зелье»

можно в любом секс-шопе. Но знаете ли вы, что и обычный парфюм, безо всяких

«привораживающих» добавок, тоже может усилить собственное очарование!

Ненавязчивый и окутывающий вас, который хочется вдыхать до бесконечности, он

усиливает сигналы, посылаемые вами потенциальному спутнику жизни. Но не злоупотребляйте

духами -- громкий хор их многочисленных композиций заглушает тоненький

голосок феромонов.

Чтобы пробудить в себе чувственность и усилить

выработку собственных половых феромонов, придуманы смеси-афродизиаки:

Для светловолосых. Смешайте сухие травы: 6

лепестков розы, столько же лепестков фиалки, по щепотке мяты и шалфея, 10

листьев вербены. Залейте 50 мл спирта и настаивайте неделю. Затем процедите.

Наносите на запястья и под колени, лучше всего после захода солнца.

Для темноволосых. В 50 мл спирта добавьте одну

чайную ложку цветов сирени, по капле эфирного масла гвоздики и жасмина. В

другую емкость с таким же количеством спирта бросьте по щепотке мяты и

базилика. Настаивайте неделю. Когда настой будет готов, наносите на запястья

по одной капле первого состава, а сверху — по капле другого. Лучше всего, по

утверждениям знатоков, «зелье» действует до полудня.

7. Школа обольщения. Если хотите понимать язык

феромонов, дышите не ртом, а носом. Причем ученые считают, что особенно

чувствительна к феромонам левая ноздря. Не сидите на строгих диетах. Иначе

организм начнет выводить через поры продукты распада белков, и кожа

приобретает специфический запах. А усиленное выделение репеллентов

красноречиво поведает окружающим об эмоциональном спаде, неизбежно сопровождающем

жертву инквизиторских диет.

8. Феромон в чистом виде. Собираясь повышать свою

сексуальность, будьте осторожны с антиперспирантами. Особенно перед

свиданием. Они приостанавливают процесс потоотделения, а вместе с ним и

выработку феромонов. Правда, впадать в другую крайность тоже не стоит. Резкий

запах пота создает серьезные помехи сексуальным посланиям, к тому же не всем

мужчинам нравится столь «жесткий натурализм». Как сказал один древнеримский

мудрец: «Лучшим ароматом женщины является естественный запах, когда от нее

ничем больше не пахнет».

9. В зачаточной форме. Мужчинам легко определить,

когда у женщины наступает наиболее благоприятный период для зачатия. Дело в

том, что при овуляции у нее меняется состав феромонов. Мужчины это чувствуют

и подсознательно у них возникает порыв подарить даме сердца, например, цветы.

Женщины тоже меняют стиль поведения. Они хотят флиртовать, носить откровенные

наряды. Существует и наглядный признак «готовности»: в этот период кожа как

бы слегка светлеет, а груди становятся более симметричными.

10. Секретное оружие. Ученые стали изучать

феромоны совсем недавно. Всего их было открыто 20, и большинство из них к

сексуальным ароматам никакого отношения не имеют. Со временем

«привораживающие» стали использовать в парфюмерии. А остальные… соблюдая

строжайшую конспирацию, изучают секретные службы. Ведь с помощью

микроскопических доз пахучих молекул можно манипулировать сознанием и

поведением человека.

Говорят, последние разработки связаны с

воздействием феромонов на память и внушение. Если в секретных лабораториях

расшифруют индивидуальный запах человека, то сильно облегчат жизнь

следователям: преступника можно будет вычислить за считанные минуты по

личному «отпечатку запахов».

А как пригодились бы феромоны в медицине! Врачи

могли бы использовать их в лечении гормональных нарушений. Кстати, уже

доказано, что запах мужского пота, насыщенного феромонами, не только улучшает

настроение женщин, но и способен… менять уровень гормона, регулирующего

репродуктивную функцию.

Для многих из нас запах тела чернокожих кажется

слишком резким. А вот для представителей монголоидной расы «бледнолицые»

пахнут просто невыносимо.

По материалам журнала «Натали»

Феромоны насекомых

Феромоны

используются насекомыми для подачи самых разных сигналов. Упомянутый

во вступлении к статье бомбикол использовался самками шелкопряда для поиска

полового партнёра, однако на этом влияние феромонов на регулирование жизни

насекомых не ограничивается. Например,

муравьи используют феромоны для обозначения пройденного

пути. По специальным меткам, оставляемым по дороге, муравей может найти

дорогу обратно в муравейник. Также, метки, делаемые при помощи феромонов

показывают муравейнику путь к найденной добыче. Отдельные запахи используются

муравьями для подачи сигнала об опасности, что провоцирует у особей либо

бегство, либо агрессивность. [править] Феромоны позвоночных

Ввиду

достаточно сложных поведенческих реакций феромоны позвоночных изучены слабо. Существует предположение,

что рецептором феромонов у позвоночных является вомероназальный (якобсонов) орган. Исследование

человеческих феромонов находится пока ещё на зачаточной стадии. Известно, что

в поте

некоторых мужчин находятся вещества, привлекающие женщин. Также

отмечено, что в больши́х женских коллективах менструальный цикл со

временем синхронизируется, протекая одновременно у большинства женщин. Эта

особенность также приписывается воздействию человеческих феромонов. [править] Применение феромонов

Феромоны

нашли своё использование в сельском хозяйстве. В сочетании с ловушками разных

типов, феромоны, приманивающие насекомых, позволяют уничтожать значительные

количества вредителей. Также, распыление феромонов над охраняемыми

сельскохозяйственными угодьями позволяет обмануть самцов вредителей и таким

образом снизить популяцию вредных насекомых — ввиду того, что самцы,

привлечённые более сильным синтетическим запахом, не смогут найти самку для

спаривания. Многие феромоны насекомых ученые научились синтезировать

искусственно. СЛАДКАЯ ВЛАСТЬ

ФЕРОМОНОВ Кандидат

биологических наук А. МАРГОЛИНА http://www.nkj.ru/archive/articles/1243/ Представьте, что вы голодны - не

так чтобы очень сильно, но мысль о еде все настойчивее вас посещает. И вдруг

доносится восхитительный аромат чего-то жареного. Моментально, словно кто-то

нажал невидимую кнопку, рот наполняется слюной, желудок "подает

голос", а чувство голода становится нестерпимым. Проследить связь между

запахом и физиологической реакцией (слюноотделение, выделение желудочных

соков) в данном случае несложно, однако стоит убрать запах (вернее, осознанную

регистрацию запаха), и все происходящее станет совершенно непонятным. Нечто там, в носу

...О чудеса природы! О

нос!...

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Abstract |

We observed the surface of the anterior part of the nasal septum of

living subjects using an endoscope. In ~13% of 1842 patients without

pathology of the septum, the vomeronasal pit was clearly observed

on each side of the septum, and in 26% it was observed only on one

side. The remaining observations indicated either the presence of

putative pits or no visible evidence of a pit. However, repetitive

observations on 764 subjects depicted changes over time, from

nothing visible to well-defined pits and vice versa. Based on 130

subjects observed at least four times, we estimate that ~73% of

the population exhibits at least one clearly defined pit on some

days. By computer tomography, the vomeronasal cavities were

located at the base of the most anterior part of the nasal septum.

Histological studies indicated that the vomeronasal cavities

consisted of a pit generally connected to a duct extending in a

posterior direction under the nasal mucosa. Many glands were

present around the duct, which contained mucus. There was no sign

of the pumping elements found in other mammalian species. Most

cells in the vomeronasal epithelium expressed keratin, a protein

not expressed by olfactory neurons. Vomeronasal epithelial cells

were not stained by an antibody against the olfactory marker

protein, a protein expressed in vomeronasal receptor neurons of

other mammals. Moreover, an antibody against protein S100, expressed

in Schwann cells, failed to reveal the existence of vomeronasal

nerve bundles that would indicate a neural connection with the

brain. Positive staining was obtained with the same antibodies on

specimens of human olfactory epithelium. The lack of neurons and

vomeronasal nerve bundles, together with the results of other

studies, suggests that the vomeronasal epithelium, unlike in other

mammals, is not a sensory organ in adult humans.

|

|

Introduction |

Frederic Ruysch discovered the vomeronasal cavities in humans in

1703 (Figure 1A). He described a ‘canalibus

nasalibus’ on each side of the anterior part of the nasal septum

of a young cadaver (Figure 1A) (Ruysch, 1703![]() ; Hollnagel-Jensen and Andreasen,

1948

; Hollnagel-Jensen and Andreasen,

1948![]() )]. Von Sömmering (Von

Sömmering, 1809

)]. Von Sömmering (Von

Sömmering, 1809![]() ) confirmed these

observations on adult cadavers and Kölliker (Kölliker, 1877

) confirmed these

observations on adult cadavers and Kölliker (Kölliker, 1877![]() ) (Figure 1B) made a detailed study of the

position of the vomeronasal cavities in the nasal septum of dead foetuses,

children and adults. In 18 adults he found these cavities

) (Figure 1B) made a detailed study of the

position of the vomeronasal cavities in the nasal septum of dead foetuses,

children and adults. In 18 adults he found these cavities ![]() ) extended these observations to

living adults. By inserting a fine stylet into visible pits (Figure 1C), he estimated the

length of the cavity to be 3–4 mm. He observed both sides of the

nasal septum of 200 living subjects and found only 100 pits, i.e.

they were present in only 25% of the observed nasal cavities.

Ludvig Jacobson described in great detail the vomeronasal organ in

a number of mammalian species [Jacobson,

) extended these observations to

living adults. By inserting a fine stylet into visible pits (Figure 1C), he estimated the

length of the cavity to be 3–4 mm. He observed both sides of the

nasal septum of 200 living subjects and found only 100 pits, i.e.

they were present in only 25% of the observed nasal cavities.

Ludvig Jacobson described in great detail the vomeronasal organ in

a number of mammalian species [Jacobson, ![]() )]. He also noted the lack

of development of the vomeronasal structure in humans and said

that the vomeronasal organ could be ‘a sensory organ which is a

sense about which human beings have no conception’. More recently,

Johnson et al. observed 100 living adults and found a

vomeronasal pit either on both sides (nine subjects) of the nasal

septum or only one side (30 subjects) (Johnson et al., 1985

)]. He also noted the lack

of development of the vomeronasal structure in humans and said

that the vomeronasal organ could be ‘a sensory organ which is a

sense about which human beings have no conception’. More recently,

Johnson et al. observed 100 living adults and found a

vomeronasal pit either on both sides (nine subjects) of the nasal

septum or only one side (30 subjects) (Johnson et al., 1985![]() ). In histological sections from

cadavers they identified at least one vomeronasal cavity in ~70%

of nasal septa. Gaafar et al. observed vomeronasal pits in ~76%

of subjects (Gaafar et al., 1998

). In histological sections from

cadavers they identified at least one vomeronasal cavity in ~70%

of nasal septa. Gaafar et al. observed vomeronasal pits in ~76%

of subjects (Gaafar et al., 1998![]() ). Other studies (Garcia-Velasco

and Mondragon, 1991

). Other studies (Garcia-Velasco

and Mondragon, 1991![]() ; Moran et al., 1991

; Moran et al., 1991![]() ; Stensaas et al., 1991

; Stensaas et al., 1991![]() ) claim that most

adults have visible bilateral vomeronasal pits, but do not give

many details about the criteria used for identification. In a

previous study (Trotier et al., 1996

) claim that most

adults have visible bilateral vomeronasal pits, but do not give

many details about the criteria used for identification. In a

previous study (Trotier et al., 1996![]() ), we observed the vomeronasal

pits in a few subjects. One aim of the present study was to obtain

a better estimate of the prevalence of vomeronasal pits using a

larger population.

), we observed the vomeronasal

pits in a few subjects. One aim of the present study was to obtain

a better estimate of the prevalence of vomeronasal pits using a

larger population.

A central question concerning the vomeronasal structure in adult humans

is its functionality. If the vomeronasal cavity were to act, like

in other mammals, as a sensory organ bringing information to the

brain it must contain receptor neurons. However, to our knowledge,

the evidence for functional vomeronasal receptor neurons connected

to the brain is very inconclusive in adult humans. Attempts to

demonstrate the existence of neurons, in adult vomeronasal

epithelia, were negative (Jordan, 1973![]() ; Johnson et al.,

1985

; Johnson et al.,

1985![]() ; Moran et al., 1991

; Moran et al., 1991![]() ; Johnson, 1998

; Johnson, 1998![]() ; Smith et al., 1998

; Smith et al., 1998![]() ), except in one study (Takami

et al., 1993

), except in one study (Takami

et al., 1993![]() ) where a few epithelial

cells, having a bipolar shape, were stained with an antibody

against neuron-specific enolase. However, the density of these

putative sensory neurons did not exceed a few immunoreactive cells

per 200 µm of vomeronasal luminal surface. Electron microscopy

studies of adult vomeronasal ducts (Stensaas et al., 1991

) where a few epithelial

cells, having a bipolar shape, were stained with an antibody

against neuron-specific enolase. However, the density of these

putative sensory neurons did not exceed a few immunoreactive cells

per 200 µm of vomeronasal luminal surface. Electron microscopy

studies of adult vomeronasal ducts (Stensaas et al., 1991![]() ; Gaafar et al., 1998

; Gaafar et al., 1998![]() ; Jahnke and Merker, 1998

; Jahnke and Merker, 1998![]() ) also suggest that

some epithelial cells could be considered as putative neurons, but

arguments are indirect and not conclusive. It seems essential that

more information must be obtained before drawing a definite conclusion

about the sensory function of the vomeronasal epithelium in adult

humans.

) also suggest that

some epithelial cells could be considered as putative neurons, but

arguments are indirect and not conclusive. It seems essential that

more information must be obtained before drawing a definite conclusion

about the sensory function of the vomeronasal epithelium in adult

humans.

|

|

Materials and methods |

Observations with the endoscope

We

observed both sides of the nasal septum of 1154 women and 877 men.

All age groups (Table 1) were represented for both genders

(15–94 years; mean age = 46 ± 17 years for men and 49 ± 16 years

for women). The endoscope used was a Storz Foreward Endoscope 0°,

Table 1 Age structure of the population of 2031

subjects observed by endoscopy

|

Age (years) |

Women |

Men |

|

|

||

|

15–24 |

79 |

103 |

|

25–34 |

182 |

154 |

|

35–44 |

186 |

151 |

|

45–54 |

268 |

170 |

|

55–64 |

238 |

164 |

|

64–74 |

156 |

99 |

|

>74 |

45 |

36 |

|

Total |

1154 |

877 |

For each subject the diagnostic of a possible pathology of the nasal

mucosa was established using appropriate clinical methods. Subjects

were gathered into the following four etiological groups: (i) no

pathology (n = 773); (ii) presence of nasal polyps (n =

402); (iii) inflammation of the mucosa due to allergy or rhinitis (n

= 667); and (iv) altered nasal septum due to perforation or

surgical modification of the anterior part of the nasal septum (n

= 189). Subjects from groups 1, 2 and 3 did not have an altered nasal

septum (n = 1842). Statistical analysis was performed using

the ![]() 2 test. Means are given ± 1 SD.

2 test. Means are given ± 1 SD.

Computer tomography

The

nasal cavities of seven patients (five males and two females; mean

age 48 years, range 15–63 years) were examined using computer

tomography after filling of the vomeronasal cavity with Iopamiron

370® (a tri-iodine water-soluble contrast substance commonly used

in radiology; Sherring-Plough, UK). For these subjects nasal

computer tomography was prescribed for medical reasons not related

to the pathology of the nasal septum. All subjects were informed

and gave their consent to this observation. The contrast substance

was injected using a sterile catheter (Venflon, 100 µm in

diameter,

Consecutive

Histology

Specimens

were collected from four fresh cadavers of subjects who have

consented to post-mortem scientific studies and from 11 patients

undergoing a surgical procedure that required a large ablation of

the tissues at the anterior part of the nasal septum. The

ablation, performed by a surgeon on patients under general

anaesthesia, was necessary for medical reasons not related to the

present study. According to the recommendations from the

Declaration of Helsinki, subjects were informed about the procedure

and gave their consent. Specimens of nasal epithelium were fixed

in buffered 3% formaldehyde or Bouin’s fixative for 2 days,

dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Serial sections (4 µm thick)

were made and stained with haematoxylin–eosin and saffron. Of the

15 specimens, nine contained a vomeronasal structure. Seven of

these were subsequently processed using various antibodies.

Immunohistochemistry

Antibodies

specific for keratin (Immunotech KL1, Marseille, France, dilution

1/50), neuron-specific enolase (Dako H14, Glostrup, Denmark,

dilution 1/100), olfactory marker protein (OMP; a gift of Prof.

Frank L. Margolis, University of Maryland, Baltimore, MD; dilution

1/600), S-100 protein (Dako Z311, polyclonal; dilution 1/500),

chromogranin A (Dako DakA3; dilution 1/100), synaptophysin (Dako

SY 38; dilution 1/20; after microwave pre-treatment of sections),

tau protein (Dako A024, polyclonal; dilution 1/200), neurofilaments

(Immunotech 1065; no dilution) and vimentin (Immunotech V9;

dilution 1/50) were used. After incubation, the fixation of the

antibody was revealed using an avidin–biotin complex peroxidase

method (Vectastain ABC kit, Vector Lab, Burlingam, CA). Several

slides at different levels of each vomeronasal structure were

incubated with each antibody. All the slides were counterstained

with haematoxylin. For all antibodies, simultaneous processing of

serial sections of adult human olfactory mucosa was performed.

Omission of the primary antibody was used as a negative control in

each case.

|

|

Results |

Endoscopy

Well-defined pits

In some cases the vomeronasal pit was found almost immediately when

looking at the antero-inferior one-third of the nasal septum with

the endoscope. It appeared as an obvious depression into the nasal

mucosa (Figure 2A–D). The size of these pits ranged

from ~1 mm to ~2.5 mm. In most of these cases, the posterior edge

(p in Figure 2) of the pit dropped much more

rapidly into the nasal mucosa than the anterior edge (a in Figure 2) and made a

well-defined ridge, with a crescent or rounded shape. For over

half of these observations the opening of the internal duct (see

below) was clearly seen. Carbon particles, when applied around the

pit, moved over the pit, transported by the flow of mucus that

moved in an antero-posterior direction. Suggestively, the mucus

did not specifically converge towards the pit.

|

In other cases (Figure 2E) the pit was also well defined

but smaller, down to ~0.3 mm. Most of the time, these small pits

became apparent only after clearing the mucus layer with a cotton pad.

Putative pits

Sometimes, well-defined pits were not found but the presence of

putative pits (Figure 2F) was suspected in the expected

region of the septum. These putative pits, of ~1–2 mm in diameter,

appeared as being nearly flush with the surface. No clear depression

into the nasal mucosa could be seen and the posterior edge was not

visible.

Absence of visible pit

In many cases nothing similar to a pit or a putative pit could be

seen at the surface of one or both sides of the nasal septum, despite

a thorough cleaning of the mucus and a careful observation of the

said region of the septum. In these cases the area of observation

was extended to all the observable surface of the septum.

|

Left

side |

Right

side |

Group

1 (no pathology) |

Group

2 (polyposis) |

Group

3 (allergy/rhinitis) |

Total

(groups 1–3) |

Group

4 (altered septum) |

|

|

||||||

|

1 |

1 |

104

(13.5%) |

64

(15.9%) |

76

(11.4%) |

244

(13.2%) |

3

(1.6%) |

|

1 |

0 |

69

(8.9%) |

31

(7.7%) |

37

(5.5%) |

137

(7.4%) |

3

(1.6%) |

|

1 |

? |

43

(5.6%) |

27

(6.7%) |

40

(6.0%) |

110

(6.0%) |

2

(1.1%) |

|

0 |

1 |

59

(7.6%) |

39

(9.7%) |

44

(6.6%) |

142

(7.7%) |

7

(3.7%) |

|

? |

1 |

33

(4.3%) |

22

(5.5%) |

32

(4.8%) |

87

(4.7%) |

7

(3.7%) |

|

0 |

0 |

320

(41.4%) |

163

(40.5%) |

307

(46.0%) |

790

(42.9%) |

149

(78.8%) |

|

0 |

? |

54

(7.0%) |

27

(6.7%) |

46

(6.9%) |

127

(6.9%) |

6

(3.2%) |

|

? |

0 |

56

(7.2%) |

20

(5.0%) |

57

(8.5%) |

133

(7.2%) |

10

(5.3%) |

|

? |

? |

35

(4.5%) |

9

(2.2%) |

28

(4.2%) |

72

(3.9%) |

2

(1.0%) |

|

Total |

|

773 |

402 |

667 |

1842 |

189 |

|

|

||||||

Prevalence of pits and putative pits

For each subject we noted, for each side of the nasal septum, ‘1’ when

a pit was present, ‘?’ when a putative pit was present and ‘0’

when no vomeronasal pit could be observed. Considering the left

and the right sides of the septum and the three possibilities

(presence of a pit, presence of a putative pit or nothing visible),

nine classes of subjects were observed. Table 2 indicates the number of subjects

in each of these classes for 773 subjects without nasal pathology,

402 subjects having nasal polyps and 667 subjects showing an inflammation

of the nasal mucosa due to allergy or rhinitis. Analysis of the

results described in Table 2 also indicates that

these two pathological groups and the reference group are homogeneous

(![]() 2 = 0.15). Therefore we pooled these three

groups to give an

2 = 0.15). Therefore we pooled these three

groups to give an

Table 2 Aspects of the vomeronasal pits at the first observation of

the left and right sides of the nasal septum of 2031 subjects

estimation

of the prevalence of the pits in 1842 subjects. It is evident from

Table 2 that less than half of the

subjects (42.9%) had no visible pit on either side of the septum

at a single observation.

In the first step of analysis, we

considered only the prevalence of clearly defined pits (such as in

Figure 2A–E). Putative pits

were not considered. In that case, one can observe that 244

subjects (13.2%) had a pit on each side of the septum, 247 subjects

(13.4%) had a pit only on the left and 229 subjects (12.4%) had a

pit only on the right. About 39% of our sample showed at least one

well-defined vomeronasal pit.

In

the second step, we included putative pits. In that case, 513

subjects (27.9%) had bilateral pits, 270 subjects (14.7%) had a

pit only on the left and 269 subjects (14.6%) a pit only on the

right. About half of the population (57%) had at least one

well-defined pit or one putative pit. No statistical difference (2

test) was observed when we considered the sex of the subjects. Analysis

made after repartitioning the subjects into classes of 10 years

age range revealed that there were no changes in frequency of the

vomeronasal pit with age.

The

probability of observing a pit, or a putative pit, in 189 patients

with an altered septum due to either nasal perforation or surgery

of the nasal septum was significantly lower (![]() 2 < 0.01) than for the group of

1842 reference subjects (Table 2). Most of them (73.4%)

had no visible vomeronasal pit on either side of the septum, 6.9%

had bilateral pits and the remaining (19.7%) had only one pit

either on the left or on the right side.

2 < 0.01) than for the group of

1842 reference subjects (Table 2). Most of them (73.4%)

had no visible vomeronasal pit on either side of the septum, 6.9%

had bilateral pits and the remaining (19.7%) had only one pit

either on the left or on the right side.

Repetition of the observations

We had the opportunity to repeat the observation of the nasal septum

on 764 subjects without any pathology of the nasal mucosa. The

time between the observations ranged from a few days to a few

months. No statistical difference (![]() 2 = 0.30) was observed between the

frequencies observed in the nine classes of Table 2 in the first and the second series,

indicating a global stability of the observations at the level of

the whole population of subjects. However, there was a variability

of the observations for some subjects. Two features were noted. A

vomeronasal pit observed on the first inspection could not be

observed on the second inspection. Conversely, a vomeronasal pit

could be observed on the second inspection where nothing could be

seen on the first inspection. More precisely, only 65.3% of the

observations remained constant between the two observations. Of

414 well-defined pits visible in the first series, 52 (12.6%)

became putative pits and 54 (13.0%) were no longer visible in the

second series. One hundred and sixty pits appeared in the second

series from 255 putative pits and from no detectable pit (n

= 859) in the first series. Of the 255 putative pits seen in the

first series, 194 were no longer visible and 69 became

well-defined pits. Ninety-one pits appeared from no detectable pit

in the first inspection. Following these observations, it is clear

that the appearance of the vomeronasal pit could change over time

for a given subject. In 130 subjects seen four times or more, at

least one vomeronasal pit could be observed in 95 subjects (73.1%)

and at least a putative pit could be observed on at least one side

in an additional 24 subjects (18.5%). No pit or putative pit could

be detected on either side of the septum in only 11 subjects

(8.5%).

2 = 0.30) was observed between the

frequencies observed in the nine classes of Table 2 in the first and the second series,

indicating a global stability of the observations at the level of

the whole population of subjects. However, there was a variability

of the observations for some subjects. Two features were noted. A

vomeronasal pit observed on the first inspection could not be

observed on the second inspection. Conversely, a vomeronasal pit

could be observed on the second inspection where nothing could be

seen on the first inspection. More precisely, only 65.3% of the

observations remained constant between the two observations. Of

414 well-defined pits visible in the first series, 52 (12.6%)

became putative pits and 54 (13.0%) were no longer visible in the

second series. One hundred and sixty pits appeared in the second

series from 255 putative pits and from no detectable pit (n

= 859) in the first series. Of the 255 putative pits seen in the

first series, 194 were no longer visible and 69 became

well-defined pits. Ninety-one pits appeared from no detectable pit

in the first inspection. Following these observations, it is clear

that the appearance of the vomeronasal pit could change over time

for a given subject. In 130 subjects seen four times or more, at

least one vomeronasal pit could be observed in 95 subjects (73.1%)

and at least a putative pit could be observed on at least one side

in an additional 24 subjects (18.5%). No pit or putative pit could

be detected on either side of the septum in only 11 subjects

(8.5%).

Computer tomography

To

get more detailed information about the position of the vomeronasal cavities

in the nasal septum, we injected a water-soluble contrast substance

into clearly visible pits of seven subjects. Computer tomography

scans were performed ~15 min after the injection, and coronal,

sagittal and axial sections of the nasal cavities were

reconstructed (Figure 3). The location of the opaque spot

indicated the position of the vomeronasal cavity. Its length ranged

from 2 to

|

Connection of the pit with the vomeronasal duct

One

of the longest vomeronasal ducts that we observed is presented in Figure 4. In this preparation the sections

were made along a plane parallel to the long axis of the duct and

perpendicular to the surface of the nasal mucosa. Therefore, both

the medial side and the lateral side of the duct were observed

simultaneously. In other mammals, the epithelium of the medial side

contains vomeronasal neurons and the lateral side is lined with

ciliated epithelium on a structure containing erectile tissue and

blood vessels, which are involved in the active pumping of the

stimuli into the lumen.

|

In Figure 4, the vomeronasal pit, in direct contact

with the nasal cavity, appeared as a funnel. The diameter and the

depth of the pit was ~600 µm. The posterior edge (p in Figure 4) of the pit deepened

rapidly into the nasal mucosa. The vomeronasal duct started at the

base of this posterior edge. Adjacent serial sections indicated

that the duct was closed, at its posterior end, after a length of

~2 mm. The lumen of the duct had a diameter of ~100 µm and contained

mucus. Many glands (arrows in Figure 4) were present on both sides of

the duct, below the epithelium lining the lateral and medial sides

of the lumen. The duct of some of these glands clearly reached the

surface of the epithelium (g in Figure 4).

In

contrast to other mammals (see Døving and Trotier, 1998![]() ), there was no sign of any

erectile tissue, large blood vessels or encapsulating cartilage

around the duct.

), there was no sign of any

erectile tissue, large blood vessels or encapsulating cartilage

around the duct.

Five

other specimens contained a similar vomeronasal structure although

the length of the duct was sometimes smaller than in Figure 4. In three additional specimens

the pit was present but the duct was very short or absent. In six

other specimens nothing similar to a vomeronasal structure could

be found.

Immunohistochemistry

Anti-keratin

In the olfactory epithelium (Figure 5, O) keratin was found in

supporting cells, located in the upper part of the epithelium, and

in cells located near the basal lamina. Bipolar olfactory receptor

neurons were not reactive and therefore their cell bodies made a

distinctive unstained layer in the lower half of the epithelium.

No such clear layer could be observed in sections of vomeronasal

ducts (Figure 5, V). The majority of cells

were stained with no obvious difference between the epithelium covering

the lateral side of the lumen and the epithelium covering the

medial side. Some epithelial cells were not stained, but they did

not form a clear layer in the epithelium. Among them, very rare

cells had a morphology that could evoke the typical bipolar shape

of vomeronasal neurons observed in all other species. It should be

emphasized that the density of these ‘bipolar cells’ was extremely

low. For example, only one cell, indicated by the arrow in Figure 5 (V) and shown in negative at

higher magnification in the picture on the right, was found in

this section of the epithelium covering the medial side of the

lumen.

|

The same observations were made from five out of the six other specimens

of vomeronasal structures; the last one was not tested.

Anti-OMP

The antibody against the olfactory marker protein stained the cytoplasm

of olfactory receptor neurons in the olfactory epithelium (Figure 6, O). These cells had a typical

bipolar shape with a long dendrite reaching the surface of the

epithelium. The same antibody applied in the same conditions

failed to stain any cell in the vomeronasal epithelium, either in

the medial epithelium or in the lateral epithelium (Figure 6, V).

|

We tested this antibody on the six other vomeronasal specimens. In

none of them could we reveal the presence of OMP-expressing cells in

the epithelia. In two specimens, glands below the epithelium were

stained.

Anti-protein S-100

The S-100 protein is a marker expressed in glial and Schwann cells

wrapping axon fascicles. Myoepithelial cells and some duct cells

of normal seromucous glands also express S-

|

This antibody was tested on five out of the six other vomeronasal specimens

(one specimen was not tested). In none of them could staining of

nerve bundles be observed.

Anti-neuron-specific enolase

This antibody stained a number of receptor neurons in the olfactory epithelium

(not shown). In four out of the seven vomeronasal structures no

staining was observed. In the remaining three specimens, a very

few epithelial cells were reactive to the antibody (not shown).

Other antibodies

Other antibodies, against vimentin, neurofilaments, glial fibrillary acidic

protein, synaptophysin, chromogranin A and tau-protein, were not

reactive either in olfactory epithelium or in the seven vomeronasal

structures.

|

|

Discussion |

Anatomy of the vomeronasal pits

In

the present study, we confirm that the opening of the vomeronasal structure

can be observed in many subjects. In some cases it made a clearly

defined depression in the nasal mucosa. The injection of a

contrast substance, followed by computer tomography, indicated that

the vomeronasal cavity was located in the enlargement seen at the

base of the nasal septum. This is exactly the position of the

vomeronasal organ in human embryos (Kjær and Fischer Hansen,

1996a). This observation is significant

because Johnson et al. showed that many small pits observed

by endoscopy to be distributed across large areas of the septum

were, in fact, the openings of glands (Johnson et al., 1985).

We

found that the antero-posterior position of the vomeronasal duct,

in computer tomographies, corresponds well with previous observations

(Figure 1) and more recent findings

(Jordan, 1973; Johnson et al.,

1985), ~2 cm from the nostril.

Originally

discovered by Ludvig Jacobson (Trotier and Døving, 1998), a cartilaginous capsule

separates, in all other mammals, the vomeronasal organ from the

nasal cavity. We did not observe such cartilage around the duct in

adult humans, which agrees with previous observations (Potiquet,

1891; Johnson et al., 1985). In addition, other mammals use

a special device, consisting of a turgescent tissue irrigated by

large and small blood vessels, to pump in and out the stimulus

present in the nasal cavity (Døving and Trotier, 1998). These elements were not

discernible in our histological material. This lack of pumping

elements has already been emphasized (Johnson et al., 1985; Jordan, 1973). We agree with

Jacobson (Trotier and Døving, 1998), who considered that

the vomeronasal structure is rudimentary or regressive in adult

humans. In a few attempts we observed, during a few minutes, that

the flow of nasal mucus was not obviously directed towards or from

the pit. Therefore one should consider that substances in the nasal

mucus might reach the vomeronasal duct only by passive diffusion.

Inspection

of the nasal septum of a given individual led to three possible

observations concerning the vomeronasal pit: the presence of a

well-defined pit, the presence of a putative pit or no pit

visible. An intriguing outcome of the present study is that the

appearance of the pit may change for a given individual depending

on the time of observation. In some cases, repetition of the

observation indicated that well-defined pits appeared where only

putative pits or even no visible pits were observed in the first

inspection. Therefore one cannot conclude the absence of a pit

when nothing is visible from a single observation; repeated

observations at different times are required. If we consider the

130 subjects observed at least four times, we can conclude that

~73% of them presented a well-defined pit on one day or another.

This percentage increases to ~91% if we consider putative pits.

A

well-defined pit may also change into a ‘putative’ pit or ‘no

visible’ pit during successive inspections. These observations

suggest the existence of an unknown mechanism that may change the

appearance of the pit and therefore reduces the possibility of

seeing it by endoscopy. In this context it is of interest that

Pearlman says: ‘Seeing the facility with which the opening of the

organ can be found in the cadaver, it is astonishing how difficult

it is to find it in the living subjects’ (Pearlman, 1934![]() ). Johnson et al. made

similar observations: in living subjects they observed that 39

nasal septa out of 100 presented at least one visible pit, whereas

histological observation from cadavers indicated that ~70% of nasal

septa presented at least one vomeronasal pit (Johnson et al.,

1985

). Johnson et al. made

similar observations: in living subjects they observed that 39

nasal septa out of 100 presented at least one visible pit, whereas

histological observation from cadavers indicated that ~70% of nasal

septa presented at least one vomeronasal pit (Johnson et al.,

1985![]() ).

).

The

probability of finding a pit or a putative pit does not depend on

obvious pathology of the nasal mucosa, such as polyposis, rhinitis

or allergy. It is only when the anterior part of the septum was

altered by perforation or surgical septoplasty that the

probability of finding pits was significantly lower. No significant

effect of age or sex was observed.

Histology of the vomeronasal epithelium

There

have been few electrophysiological studies aimed at revealing nervous

activity of the vomeronasal cavity in humans. A negative shift of

the surface potential of the pit was recorded following application

of putative human pheromones (Monti-Bloch and Gosser, 1991![]() ; Monti-Bloch et al., 1994

; Monti-Bloch et al., 1994![]() ). By analogy with the slow

voltage change evoked by odorants at the surface of the olfactory

epithelium, this electrical signal has been considered by the

authors as the receptor potential induced by activation of

vomeronasal receptor neurons. According to this interpretation,

the activation of the vomeronasal pit may trigger autonomic responses

and modifications of the blood level of some hormones (Berliner

et al., 1996

). By analogy with the slow

voltage change evoked by odorants at the surface of the olfactory

epithelium, this electrical signal has been considered by the

authors as the receptor potential induced by activation of

vomeronasal receptor neurons. According to this interpretation,

the activation of the vomeronasal pit may trigger autonomic responses

and modifications of the blood level of some hormones (Berliner

et al., 1996![]() ; Monti-Bloch et al.,

1998a

; Monti-Bloch et al.,

1998a![]() ,b

,b![]() ). However, to our knowledge, the

existence of functional vomeronasal receptor neurons that connect to

the brain is doubtful in adult humans (Jordan, 1973

). However, to our knowledge, the

existence of functional vomeronasal receptor neurons that connect to

the brain is doubtful in adult humans (Jordan, 1973![]() ; Johnson et al.,

1985

; Johnson et al.,

1985![]() ; Moran et al., 1991

; Moran et al., 1991![]() ; Johnson, 1998

; Johnson, 1998![]() ; Smith et al., 1998

; Smith et al., 1998![]() ). The immunohistochemistry shown

here demonstrates the absence both of OMP and of glial elements

essential for the wrapping of the unmyelinated vomeronasal axons.

). The immunohistochemistry shown

here demonstrates the absence both of OMP and of glial elements

essential for the wrapping of the unmyelinated vomeronasal axons.

It

has been demonstrated that OMP is a protein that is found in

mature neurons in the olfactory epithelium (Buiakova et al., 1994![]() ; Krishna et al., 1995

; Krishna et al., 1995![]() ; Walters et al., 1996

; Walters et al., 1996![]() ) and in the vomeronasal

organ of other species (Johnson et al., 1993

) and in the vomeronasal

organ of other species (Johnson et al., 1993![]() ; Berghard et al.,

1996

; Berghard et al.,

1996![]() ; Liman and Corey, 1996

; Liman and Corey, 1996![]() ). Therefore if mature vomeronasal

neurons exist in adult humans it should be possible to demonstrate

OMP. However, in the present study no staining was found in the

vomeronasal epithelia using an antibody against OMP. In other

species, new vomeronasal receptor neurons grow out from progenitor

cells (Barber and Raisman, 1978

). Therefore if mature vomeronasal

neurons exist in adult humans it should be possible to demonstrate

OMP. However, in the present study no staining was found in the

vomeronasal epithelia using an antibody against OMP. In other

species, new vomeronasal receptor neurons grow out from progenitor

cells (Barber and Raisman, 1978![]() ; Wang and Halpern, 1988

; Wang and Halpern, 1988![]() ). If this renewal process exists

in adult humans, some new immature receptor neurons may appear

from time to time. That could explain why some intraepithelial

cells, having a typical bipolar shape, can be observed when

histological sections are stained with an antibody against

neuron-specific enolase (Takami et al., 1993

). If this renewal process exists

in adult humans, some new immature receptor neurons may appear

from time to time. That could explain why some intraepithelial

cells, having a typical bipolar shape, can be observed when

histological sections are stained with an antibody against

neuron-specific enolase (Takami et al., 1993![]() ) or remain unstained with

anti-keratin antibody (Figure 5, V). However, these putative

immature neurons are present at a very low density that seems

quite problematic for eliciting any surface potential change

during chemical stimulations.

) or remain unstained with

anti-keratin antibody (Figure 5, V). However, these putative

immature neurons are present at a very low density that seems

quite problematic for eliciting any surface potential change

during chemical stimulations.

The

presence of a few neuron-like cells in the adult vomeronasal epithelium

does not imply that a message is sent to the brain. For doing so,

vomeronasal neurons must be connected to the accessory olfactory

bulb. Ensheathing glial cells expressing S-100 are present around

vomeronasal nerve fibres in other species (Astic et al.,

1998![]() ). In the present study we did not

find vomeronasal nerve bundles using a specific antibody against

S-100 protein whereas olfactory nerve bundles were stained. In

this context, it is difficult to assign a sensory function to the

vomeronasal epithelium of human adults.

). In the present study we did not

find vomeronasal nerve bundles using a specific antibody against

S-100 protein whereas olfactory nerve bundles were stained. In

this context, it is difficult to assign a sensory function to the

vomeronasal epithelium of human adults.

From embryos to adults

The

vomeronasal ducts develop in human embryos (Bossy, 1980![]() ; Kreutzer and Jafek,

1980

; Kreutzer and Jafek,

1980![]() ). According to Boehm and Gasser

(Boehm and Gasser, 1993

). According to Boehm and Gasser

(Boehm and Gasser, 1993![]() ), at 12 and 23 weeks of gestation

the vomeronasal epithelium contains clusters of neuron-specific

enolase-positive cells looking like olfactory receptors; at 36

weeks the organ is lined by a respiratory epithelium and does not

show any receptor-like cells. Ortmann (Ortmann, 1989

), at 12 and 23 weeks of gestation

the vomeronasal epithelium contains clusters of neuron-specific

enolase-positive cells looking like olfactory receptors; at 36

weeks the organ is lined by a respiratory epithelium and does not

show any receptor-like cells. Ortmann (Ortmann, 1989![]() ) found receptor cells in four

out of seven foetal vomeronasal organs (11–18 weeks). Luteinizing

hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH)-immunoreactive cells are detected

in the bilateral vomeronasal organs at 8–12 gestational weeks

(Kjær and Fischer Hansen, 1996a

) found receptor cells in four

out of seven foetal vomeronasal organs (11–18 weeks). Luteinizing

hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH)-immunoreactive cells are detected

in the bilateral vomeronasal organs at 8–12 gestational weeks

(Kjær and Fischer Hansen, 1996a![]() ) and in the nerve

fascicles arising from the organ to the olfactory bulb (Boehm

et al., 1994

) and in the nerve

fascicles arising from the organ to the olfactory bulb (Boehm

et al., 1994![]() ; Kjær and Fischer Hansen,

1996b

; Kjær and Fischer Hansen,

1996b![]() ). As in other mammals,

LHRH-secreting neurons migrate from the olfactory placode to the

brain during the early stages of foetal life, following

vomeronasal and terminal nerve fibres (Schwanzel-Fukuda et al.,

1996

). As in other mammals,

LHRH-secreting neurons migrate from the olfactory placode to the

brain during the early stages of foetal life, following

vomeronasal and terminal nerve fibres (Schwanzel-Fukuda et al.,

1996![]() ). In some foetuses (10–12 weeks)

the vomeronasal organ is clearly dissolving; in 17- to 19-week-old

foetuses the vomeronasal organ may not be found (Kjær and

Fischer Hansen, 1996a

). In some foetuses (10–12 weeks)

the vomeronasal organ is clearly dissolving; in 17- to 19-week-old

foetuses the vomeronasal organ may not be found (Kjær and

Fischer Hansen, 1996a![]() ). The development of the

vomeronasal structures seems to be limited to the embryonic stage,

when they play a role for the migration of LHRH-secreting cells

towards the brain.

). The development of the

vomeronasal structures seems to be limited to the embryonic stage,

when they play a role for the migration of LHRH-secreting cells

towards the brain.

In

all other species, vomeronasal receptor axons make synaptic contact

with secondary neurons in the accessory olfactory bulb. In human

foetuses, the accessory olfactory bulb is present at 8 weeks

(Bossy, 1980![]() ), 18 weeks (Humphrey, 1940

), 18 weeks (Humphrey, 1940![]() ; Meisami and Bathnagar,

1998

; Meisami and Bathnagar,

1998![]() ) and 26 weeks (Humphrey, 1940

) and 26 weeks (Humphrey, 1940![]() ). However, in older

foetuses the accessory olfactory bulb regresses and, indeed, is not

found in the adult human [for a review see (Meisami and Bathnagar,

1998

). However, in older

foetuses the accessory olfactory bulb regresses and, indeed, is not

found in the adult human [for a review see (Meisami and Bathnagar,

1998![]() )].

)].

|

|

Conclusion |

The present study has given anatomical, histological and immunohistochemical

data that all indicate that in adult humans the vomeronasal structure

is a remnant of the vomeronasal organ found in mammals. This

statement is in accordance with findings and opinions of previous

authors as discussed above. In our opinion, a viable function of

receptor neurons has never been convincingly demonstrated. We

consider that the vomeronasal structure does not function as a

sensory organ in adult humans. In conclusion, the vomeronasal structure

might have a function only during human foetal life in

contributing, together with the terminal nerve and other structures,

to the migration of neurosecretory cells containing LHRH to their

proper sites in the brain.

http://chemse.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/25/4/369

|

Abstract |

The human vomeronasal organ (VNO) has been the subject of some interest

in the scientific literature and of considerable speculation in the

popular science literature. A function for the human VNO has been

both dismissed with ridicule and averred with conviction. This

question of VNO function has been needlessly tied to the separate

question of whether there is any place for pheromone communication

among humans, a topic that is itself bogged down in conflicting

definitions. This review is an attempt to weigh the evidence for

and against human VNO function, to deconvolve that question from

the question of pheromone communication and finally to provide a

working definition of ‘pheromone’. Further experimental work is

required to resolve the conflicting evidence for and against human

VNO function but chemical communication does appear to occur among

humans. However, several examples reported in the literature do

not meet the proposed definition for communication by pheromones:

‘chemical substances released by one member of a species as

communication with another member, to their mutual benefit’.

|

|

Introduction |

The vomeronasal organ (VNO) is the peripheral sensory organ of the

accessory olfactory system. The paired organs are located at the base

of the nasal septum or in the roof of the mouth in most amphibia,

reptiles and mammals. There are numerous examples of vomeronasal

involvement in chemical communication, although pheromone

communication is not the exclusive province of the vomeronasal

system. The increase in serum luteinizing hormone and testosterone

when male mice and hamsters are exposed to chemosensory stimuli

from females appears to be absolutely dependent on vomeronasal

integrity (Coquelin et al., 1984![]() ; Pfeiffer and Johnston,

1994

; Pfeiffer and Johnston,

1994![]() ). Induction of uterine growth and

estrus in female prairie voles normally resulting from exposure to

males is also dependent on an intact VNO (Tubbiola and Wysocki,

1997

). Induction of uterine growth and

estrus in female prairie voles normally resulting from exposure to

males is also dependent on an intact VNO (Tubbiola and Wysocki,

1997![]() ). There are numerous

other behaviors and physiological responses where both vomeronasal

and olfactory inputs contribute (Wysocki and Meredith, 1987

). There are numerous

other behaviors and physiological responses where both vomeronasal

and olfactory inputs contribute (Wysocki and Meredith, 1987![]() ; Johnston, 1998

; Johnston, 1998![]() ) and some where the main

olfactory system seems to be critical (see below). In some

non-mammalian species, for example in snakes, vomeronasal

chemoreception may be used for tracking prey (Halpern, 1987

) and some where the main

olfactory system seems to be critical (see below). In some

non-mammalian species, for example in snakes, vomeronasal

chemoreception may be used for tracking prey (Halpern, 1987![]() ), which is unlikely to

be a pheromone function. Whether the vomeronasal systems in

mammals have any similar non-social communication functions has

not been thoroughly investigated. In humans there has been a

long-standing dispute over whether there is a VNO at all in adults.

Recent endoscopic and microscopic observations suggest that there

is an organ on at least one side in most adults. This

review enquires into its function.

), which is unlikely to

be a pheromone function. Whether the vomeronasal systems in

mammals have any similar non-social communication functions has

not been thoroughly investigated. In humans there has been a

long-standing dispute over whether there is a VNO at all in adults.

Recent endoscopic and microscopic observations suggest that there

is an organ on at least one side in most adults. This

review enquires into its function.

|

|

Description:

anatomical, developmental and genetic evidence |

Structure

The

existence of a VNO in the human embryo similar to the VNOs of

other species is undisputed (Boehm and Gasser, 1993![]() ). It contains bipolar

cells similar to the developing vomeronasal sensory neurons of

other species and also generates luteinizing hormone releasing

hormone (LHRH)-producing cells as in other species (Boehm et al.,

1994

). It contains bipolar

cells similar to the developing vomeronasal sensory neurons of

other species and also generates luteinizing hormone releasing

hormone (LHRH)-producing cells as in other species (Boehm et al.,

1994![]() ; Kajer and Fischer Hansen, 1996

; Kajer and Fischer Hansen, 1996![]() ). These authors showed

the structure becoming more simplified later in development. The

latter were unable to find any VNO structure at later stages (19

weeks), although others have shown a simplified but clear VNO

continuing to increase in size up to at least 30 weeks (Bohm and

Gasser, 1993

). These authors showed

the structure becoming more simplified later in development. The

latter were unable to find any VNO structure at later stages (19

weeks), although others have shown a simplified but clear VNO

continuing to increase in size up to at least 30 weeks (Bohm and

Gasser, 1993![]() ; Smith et al., 1997

; Smith et al., 1997![]() ). Numerous reports of

a structure identified as the VNO in the nasal septum in adult

humans agree that it is a blind ending diverticulum in the septal

mucosa opening via a depression (the VNO pit) into the nasal

cavity

). Numerous reports of

a structure identified as the VNO in the nasal septum in adult

humans agree that it is a blind ending diverticulum in the septal

mucosa opening via a depression (the VNO pit) into the nasal

cavity ![]() 2 cm in from the nostril. The

location of this structure is consistent with the location of the

VNO in embryos (Trotier et al., 2000

2 cm in from the nostril. The

location of this structure is consistent with the location of the

VNO in embryos (Trotier et al., 2000![]() ) and it has a similar simplified

form, with no large blood vessels, cavernous sinuses or supporting

cartilage. The structure is reported at least unilaterally in 90%

or more of subjects in some reports or in 50% or fewer in other

reports. Trotier et al. recently demonstrated that the

endoscopic appearance of the VNO pit can vary, unequivocal on one

inspection and invisible on a later inspection, or vice versa

(Trotier et al., 2000

) and it has a similar simplified

form, with no large blood vessels, cavernous sinuses or supporting

cartilage. The structure is reported at least unilaterally in 90%

or more of subjects in some reports or in 50% or fewer in other

reports. Trotier et al. recently demonstrated that the

endoscopic appearance of the VNO pit can vary, unequivocal on one

inspection and invisible on a later inspection, or vice versa

(Trotier et al., 2000![]() ). The real percentage of

individuals with at least one VNO pit may thus be underestimated

in many studies. Trotier et al. estimate

). The real percentage of

individuals with at least one VNO pit may thus be underestimated

in many studies. Trotier et al. estimate ![]() 92% with some evidence of at least

one VNO pit in subjects with no septal surgery examined multiple

times, but a substantially lower number after septal surgery

(Trotier et al., 2000

92% with some evidence of at least

one VNO pit in subjects with no septal surgery examined multiple

times, but a substantially lower number after septal surgery

(Trotier et al., 2000![]() ). Standard septal surgery may

remove the VNOs and there are anecdotal reports of adverse effects

of vomeronasal removal, but no systematic study. In histological studies

in cadavers or in septal tissue removed during nasal surgery,

several authors (Moran et al., 1991

). Standard septal surgery may

remove the VNOs and there are anecdotal reports of adverse effects

of vomeronasal removal, but no systematic study. In histological studies

in cadavers or in septal tissue removed during nasal surgery,

several authors (Moran et al., 1991![]() ; Johnson et al., 1994

; Johnson et al., 1994![]() ; Trotier et al., 2000

; Trotier et al., 2000![]() ) describe a blind ending tube

lined on all sides by a pseudo-stratified epithelium and with

associated submucosal glands. It seems highly likely that this

structure is the adult human remnant of the vomeronasal organ. Use

of the word organ in this context does not presuppose function.

) describe a blind ending tube

lined on all sides by a pseudo-stratified epithelium and with

associated submucosal glands. It seems highly likely that this

structure is the adult human remnant of the vomeronasal organ. Use

of the word organ in this context does not presuppose function.

Best case:

The vast majority of human adults have a VNO.

Worst case:

There is a diverticulum of the nasal epithelium which happens to

be remarkably consistently located at the expected position of the

VNO.

Opinion:

There is an adult human VNO.

Microanatomy

The

epithelium lining the human VNO is unlike that of VNOs in other

species and unlike that of olfactory or respiratory epithelium in

humans (Moran et al., 1991![]() ; Stensaas et al., 1991

; Stensaas et al., 1991![]() ). There are many

elongated cells presenting a microvillar surface to the lumen of

the organ but most are not similar to microvillar vomeronasal

sensory organs (VSNs) of other species. They have not been shown

to have axons leaving the epithelium nor to make synaptic contact

with axons in the epithelium, so if they are chemosensitive they

have no obvious way of communication with the brain.

). There are many

elongated cells presenting a microvillar surface to the lumen of

the organ but most are not similar to microvillar vomeronasal

sensory organs (VSNs) of other species. They have not been shown

to have axons leaving the epithelium nor to make synaptic contact

with axons in the epithelium, so if they are chemosensitive they

have no obvious way of communication with the brain.

Two

studies of the adult human vomeronasal epithelium have reported the

presence of bipolar cells resembling the VSNs found in other species

and in early human embryos. These cells contain marker substances

characteristic of neural cells. Takami et al. and Trotier

et al. found neuron-specific enolase (NSE) staining in these

cells (Takami et al., 1993![]() ; Trotier et al., 2000

; Trotier et al., 2000![]() ). It is clear from

both reports that the number of such cells is small:

). It is clear from

both reports that the number of such cells is small: ![]() 4 per 100 µm epithelial surface

(Takami et al., 1993

4 per 100 µm epithelial surface

(Takami et al., 1993![]() ) or less (Trotier et al.,

2000

) or less (Trotier et al.,

2000![]() ). Neither found the olfactory

marker protein (OMP) staining characteristic of VSNs of all other

species studied. No one has been able to show that these VSN-like cells

in the adult human VNO taper down to form axons at their basal

ends. Axons are observed in the epithelium (Stensaas et al.,

1991

). Neither found the olfactory

marker protein (OMP) staining characteristic of VSNs of all other

species studied. No one has been able to show that these VSN-like cells

in the adult human VNO taper down to form axons at their basal

ends. Axons are observed in the epithelium (Stensaas et al.,

1991![]() ), but not in continuity or in

synaptic contact with epithelial cells. Axon bundles are reported

in the submucosa (Stensaas et al., 1991

), but not in continuity or in

synaptic contact with epithelial cells. Axon bundles are reported

in the submucosa (Stensaas et al., 1991![]() ), but do not appear to arise from

axon bundles penetrating the lamina propria in the same way as in

vomeronasal epithelia of other species. Moreover, the fact that a

few human VNO cells show a morphological resemblance to VSNs does

not preclude chemosensitivity in other cell types. The human

vomeronasal epithelium differs in appearance from both the sensory

and non-sensory epithelia in the VNOs of other species and from

nasal ‘respiratory’ epithelium (Moran et al., 1991

), but do not appear to arise from

axon bundles penetrating the lamina propria in the same way as in

vomeronasal epithelia of other species. Moreover, the fact that a

few human VNO cells show a morphological resemblance to VSNs does

not preclude chemosensitivity in other cell types. The human

vomeronasal epithelium differs in appearance from both the sensory

and non-sensory epithelia in the VNOs of other species and from

nasal ‘respiratory’ epithelium (Moran et al., 1991![]() ; Stensaas et al., 1991

; Stensaas et al., 1991![]() ). The function of the cells is

not immediately obvious from their morphology. However, the absence

of OMP and any reports of putative vomeronasal receptor genes (see

below) means that any such cells are quite different from known

VSNs in other species.

). The function of the cells is

not immediately obvious from their morphology. However, the absence

of OMP and any reports of putative vomeronasal receptor genes (see

below) means that any such cells are quite different from known

VSNs in other species.

Best case:

The human VNO contains cells resembling sensory neurons even

though these do not show many of the other characteristics of VSNs

in other species and no axons have been identified. (Speculative)

Other cells might conceivably be chemosensitive, even though there

is no evidence for this in the morphology or characteristic

staining patterns of any other cell type.

Worst case:

The human VNO is devoid of neurons showing the characteristics of

VSNs in other species and devoid of other cells with clear axons

leaving the vomeronasal epithelium.

Opinion:

There are no obvious sensory neurons.

Putative receptor gene expression

Recent

evidence (Dulac and Axel, 1995![]() ; Herrada and Dulac, 1997

; Herrada and Dulac, 1997![]() ; Matsunami and Buck,

1997

; Matsunami and Buck,

1997![]() ; Ryba and Tirrindelli, 1997

; Ryba and Tirrindelli, 1997![]() ) suggests that

mammalian species with functional VNOs express two families of genes

(V1R and V2R) that appear to code for ‘seven transmembrane domain’

membrane proteins thought to be the chemoreceptor molecules

themselves. These genes are expressed in VSNs and are similar in

apparent transmembrane organization to olfactory receptor genes

(Buck and Axel, 1991

) suggests that

mammalian species with functional VNOs express two families of genes

(V1R and V2R) that appear to code for ‘seven transmembrane domain’

membrane proteins thought to be the chemoreceptor molecules

themselves. These genes are expressed in VSNs and are similar in

apparent transmembrane organization to olfactory receptor genes

(Buck and Axel, 1991![]() ), but differ in much

of their DNA sequence. These genes were labeled ‘putative pheromone

receptor genes’, although at the time of their discovery the

evidence that they might code for pheromone receptor molecules was

tenuous. Their expression in the vomeronasal epithelium is no

guarantee: some pheromones are clearly detected by the main

olfactory system (see below) and possible non-pheromone functions

of the vomeronasal system (as in snakes) have not been

investigated. Recently, Leinders-Zufall et al. showed physiological

responses in mouse VSNs to substances reported to be pheromones in

that species (Leinders-Zufall et al., 2000

), but differ in much

of their DNA sequence. These genes were labeled ‘putative pheromone

receptor genes’, although at the time of their discovery the

evidence that they might code for pheromone receptor molecules was

tenuous. Their expression in the vomeronasal epithelium is no

guarantee: some pheromones are clearly detected by the main

olfactory system (see below) and possible non-pheromone functions

of the vomeronasal system (as in snakes) have not been

investigated. Recently, Leinders-Zufall et al. showed physiological

responses in mouse VSNs to substances reported to be pheromones in

that species (Leinders-Zufall et al., 2000![]() ). The responsive neurons

were in the apical zone of the vomeronasal epithelium where most

neurons appear to express members of the V1R class of putative

vomeronasal receptor genes. This is the best evidence yet that

some members of this gene family might be pheromone receptors. The

neurons were extremely sensitive and highly selective, characteristics

we have come to expect for pheromone receptor neurons in insects.

Electrical responses to urine of VSNs (Holy et al., 2000

). The responsive neurons

were in the apical zone of the vomeronasal epithelium where most

neurons appear to express members of the V1R class of putative

vomeronasal receptor genes. This is the best evidence yet that

some members of this gene family might be pheromone receptors. The

neurons were extremely sensitive and highly selective, characteristics

we have come to expect for pheromone receptor neurons in insects.

Electrical responses to urine of VSNs (Holy et al., 2000![]() ) provide some supporting

evidence, but this report does not address the questions of which

sensory neuron types respond nor which components of urine are

stimulatory.

) provide some supporting

evidence, but this report does not address the questions of which

sensory neuron types respond nor which components of urine are

stimulatory.

Genes

similar to the vomeronasal receptor genes are also present in the

human genome. Those found in initial searches through the genome